The 10th Special Exhibition: Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing “Wanting to Preserve Memories of that Day: Dictated Accounts of the Atomic Bombing”

Carrying Away Bodies in Post-atomic-bombing Nagasaki

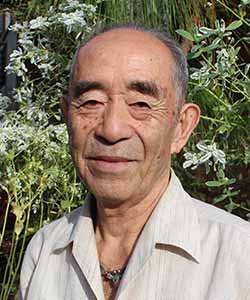

As told by Masayuki Matsuo (89 years old)

| Mr. Matsuo was born in Shimokurosaki-machi, a locality some 30 kilometers northwest of the atomic bombing hypocenter which has now been incorporated into Nagasaki City. He was fifteen years old when the atomic bomb was dropped. There was no direct damage to Kurosaki district, but Mr. Matsuo says, “The sky lit up with a flash and there was a resounding boom.” The next day he joined a volunteer unit and went to Nagasaki to provide help. He then became engaged in efforts to haul out bodies from under the wreckage. |

|---|

Life at the Beginning of the Pacific War

I was born on November 10, 1939 in what is now called Kurosaki-machi, Nagasaki City. (At the time of the atomic bombing it was called Kurosaki Village, Nishisonogi County.) I was raised there as well. My father’s name was Shige-ichi and my mother’s was Omo. I was the oldest of six brothers and sisters. On December 8, 1941, the day the Great East Asia War (the Pacific War) broke out, I was a sixth-grade student at national elementary school. The start of the war meant that we stopped having classes at school and instead we did things like work in the fields. All the rice we harvested was for soldiers and had to be delivered to the government. We also provided the army with bark stripped from mulberry or palm trees, which they used some purpose that I don’t know. In our area, no one had to be evacuated for safety.

Before being recruited into the army my father had gone to Shanghai on business. The company was called Kawanami Salvage and their business involved the raising of sunken cargo ships. I think my father was about fifty years old at that time. He received his draft papers while he was in Shanghai and promptly joined the Ainoura Naval Unit without returning home to Kurosaki.

As all the young adults were off fighting in the war, it was the older people of Kurosaki who prepared for a possible landing of American forces. They sharpened sticks of bamboo into weapons so they could stab people to death if necessary.

As there was farmland in Kurosaki, we had food throughout the war. We were never short of wheat or potatoes and people from Nagasaki would even come to buy things from us.

Our area didn’t suffer many air raids, but we did see B-29s on occasion. One time, probably by mistake, bombs were dropped up in the uninhabited mountains nearby. I was told by the town office to go and clear up the wreckage, so I went and hauled out bomb fragments and strips of metal.

Another time, when soldiers headed for the warfront were setting off from Kurosaki by boat, a B-29 spotted their vessel and flew in on attack, leaving a number of people wounded. Small boasts went out to try to rescue them, but the lives of some of those men were lost before the ever reached the battle lines.

The Atomic Bombing of August 9, 1945 and the Clearing Away of Bodies

On August 9, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing, I was at the town office. When the (morning) air-raid alert was lifted I set off for home. Then the sky lit up with a flash and a ferocious bang echoed out. The Kurosaki area was quite a way from Nagasaki, so there were no blast winds.

We received news that Nagasaki had been bombed and the next evening a volunteer relief unit of twenty or thirty men who could go and provide aid was assembled. I was the youngest member of the unit, being just fifteen years old at the time. All the young men were off fighting in the war, so the rest of the unit was made up of older men.

We travelled offshore from Kurosaki on small boats and then boarded a patrol ship that took us to Nagasaki. We carried firefighter’s hooks and stretchers with us. The ship landed at Ohato port in Nagasaki. At that time, Nagasaki was still covered in smoke. I don’t know exactly what kind of odor was in the air, but I remember that the smell was really strong. There was something horrible about the situation and I felt awful.

We spent the night in an air-raid shelter and then boarded a truck the next morning and headed for the Shiroyama district. Hardly anyone was alive there. Cows and horses were lying on their backs with their stomachs swollen up. The rice fields were filled with dead people. In the river at Ohashi I saw the body of a pregnant woman who looked as if she had been close to giving birth.

As we headed on, we came across wounded people who pleaded, “Give me a drink of water,” but the older people said, “Don’t do it!” I felt sorry for them and wanted to give them something to drink, but we didn’t have any water to spare.

Our unit went to work placing dead bodies on stretchers and carrying them to the cremation sites. We pulled corpses out of collapsed houses and took them with us. We put them on stretchers one after another and carried them away, but we had no idea who they were or what their names were.

Along the way, we saw B-29s flying in on reconnaissance, and at those times we would crawl under metal sheets or piles of wreckage and hide. We also talked about how we thought more bombs might be dropped.

It was hard work hauling off those bodies. If we grasped them by the arms the skin would come sliding right off. At first I was so scared that I couldn’t go about my job, but gradually I got used to it. The smell wafted everywhere and was really horrendous.

That night, we laid boards on the ground of the bomb shelter at Ibinokuchi and slept there. The second day we went to Takenokubo, near the area now called Haruki, and carried away more bodies. By the second day we weren’t scared anymore and stoically went about our work. Rice balls made in (the neighboring city of) Isahaya were delivered to us, but they soon went bad in the August heat. As that was all we had, we ate them anyway.

Many people died inside wells. As I was the youngest member of our group, I would be lowered into the wells with a rope wrapped around my waist and then tie up the corpses so they could be pulled up. Over and over I was sent down into those wells. Of all the people we found, not a single one was alive.

Our unit worked for two days. We had taken a boat to get to Nagasaki, but to get back home to Kurosaki we walked for a full day. There were other units from surrounding areas that also went to Nagasaki to provide relief in addition to our Kurosaki unit, but apparently they all came back after one day.

When I got back home my mother burned all the clothes I had been wearing. I guess the stench clung to them and they smelled absolutely horrendous.

Having carried off (dead bodies) after the atomic bombing, I was now used to handling corpses and when the headless body of a local soldier washed up on shore I was the one who cremated it to ashes. I imagine that soldier had been killed by a torpedo. We were able to identify him because he had been wearing a uniform. In those days, the corpses of soldiers would often wash ashore.

After doing my duty in Nagasaki, I regularly went to a nearby hospital to get preventative shots. Of those who went to Nagasaki with our group, some passed away soon after. One of my wife’s relatives went to Nagasaki after the atomic bombing to look for family members and passed away not much later. I was the youngest member of the volunteer civil defense unit that went to help out in Nagasaki and all the others who went with me have now passed away.

The Cremation Site

Although I carried hundreds of dead bodies to the cremation site over the course of those two days, I cannot for the life of me remember where it was. Mr. Sanae Ikeda, a man who now speaks about his atomic bombing experiences, carried his deceased younger brother on his back to that same cremation site. After the war, I asked Mr. Ikeda, “Where on earth was that open space by the river that served as the cremation site in those days?” but neither of us could remember.

At the cremation site, bodies were only divided into males and females. Whether the body belonged to a newly-born baby or an elderly person didn’t matter, only whether it was male or female. The bodies we gathered up were cremated by a different group of people. I think it was probably people from City Hall who did that. We only carried the bodies of the dead.

As for the remains, surviving relatives who came to City Hall to look for them were told, “If it was a male they are in this pile; if it was a female you can take them from this pile.” As the only division was by gender, nobody knew exactly whose remains they were taking home with them. I had also lost relatives to the atomic bombing and walked all the way to Nagasaki to collect their remains. I made constant trips between the prefectural office and City Hall.

After War’s End

As there was farmland in our region, we did not suffer for food after war’s end. People from Nagasaki even hiked over Nameshi Pass to come and buy things from us. Among them were women who carried babies on their backs. The food they finally managed to get their hands on was sometimes confiscated by the police or other authorities, as purchasing things that way was considered a crime in those days. And what do you think was done with the food that was seized?

After the war I had no shoes and wore only straw or wooden sandals that had straw toe straps as well. Rocks would get stuck in the straw because none of the roads were paved and sometimes I only had one sandal and walked around with the other foot bare. Some years later the rationing of shoes began, but there were not enough to go around so they held raffles for them.

Even though the war had ended, I could not go back to school. Instead I went to work for people who owned large fields, helping them grow potatoes and wheat.

As an adult, I worked at steel mills and took jobs as a construction worker. I went to work at Matsushima Construction and the coal mine on Ikeshima Island. In 1955, I married my wife and we have lived in Kurosaki ever since.

Previously, I had an operation for lung cancer. Now I go to Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Hospital twice a year for check-ups. (Unlike many others) I never suffered from illness in the time immediately after the atomic bombing. Sadly, some of the people who went to Nagasaki right after the bomb was dropped could not prove they had been there and grew sick and died without ever receiving bombing survivors’ health policies.

Message for the Young Generation

We must never have war again. Hardships continue even after war ends, as you don’t have any food or other products. We are all human, so we must get along with each other. The best thing is not to discriminate; not against the citizens of any country and not against any kind of people.

Dictated at the speaker’s home in Shimokurosaki-machi, Nagasaki City Oct. 8, 2019

An aerial view of the area around Shiroyama National Elementary School

An aerial view of the area around Shiroyama National Elementary School

U.S. Forces photograph

Property of Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

I’m glad I Survived

As told by Daijiroh Urakawa (86 years old)

| Mr. Urakawa was born and raised in the Katafuchi neighborhood of Nagasaki City. A sixth-grade student at Kami-nagasaki National Elementary School at the time of the atomic bombing, he was working as a mobilized student and was up in the hillside of Nishiyama when the bomb exploded. He and his fellow students made their way down to the reservoir, where the road was covered over with bodies. It was a hellish sight and they couldn’t tell who was alive and who was dead. He spoke about the war and the atomic bombing, both of which had a profound effect on his life and the lives of his family members and friends. |  |

|---|

Before the Atomic Bombing

I was born on June 10, 1933 and grew up in my place of birth – the Katafuchi neighborhood of Nagasaki City. Seven of us lived together; my father, my mother, my grandmother, my three older sisters and me. My older brother had gone off to fight as a soldier. I was born prematurely and was spindly child up until the third grade. I was always at the front when they lined us kids up in order of height.

My ancestors have been farmers for generations, going back some 400 years. For that reason we always had food, even during the war. Half of the kids in my class did not have enough to eat and the teachers at the national elementary school would come to my home to collect foodstuffs. That may have been the reason I was chosen to be class president.

At school, we trained to fight with bamboo spears. We would sharpen the ends of bamboo sticks and sear them over flames until they were slightly charred, and then rush together at stuffed dummies while crying out “Yaaah!” I wondered if there was any use in training with bamboo spears, but as the instructor was an army man and the drills were compulsory we couldn’t refuse to take part. We also underwent drills in which we would aim at airplanes with mock anti-aircraft guns made of wood.

Even before the atomic bombing, B-29s had been flying in and dropping firebombs. (One time) the bombs they were trying to drop on the city center mistakenly fell between Mt. Hiko and Mt. Hoka. I think there would have been horrendous fires if they had landed on the city. The firebombs had five-meter-long ribbons attached to them in order to make sure they fell straight down. The ribbons were beautiful and I went to Mt. Hoka to try to get some, but most of them got caught in the trees and didn’t fall to the ground.

As part of student mobilization efforts, I would climb the mountain at Nishiyama to collect pine resin. At my school there were three classes; one class for boys, one class for girls and one mixed class. I was in the class for boys. Nishiyama was a pine-forested area full of huge trees. We would scrape the pine trees and collect the resin that dripped down, putting it in buckets that we carried back to the school. I heard that the pine resin was being used as airplane fuel, but I’m not sure if that was true or not. We set off for Nishiyama with our lunches each morning and stayed there until evening. It wasn’t exactly heavy labor, but the climb up to the pine forest used to take us about half an hour.

The Day of the Atomic Bombing

On August 9, I once again went up to Nishiyama with the other mobilized students. We took a narrow, three-meter-wide military road that was designed for transporting army troops. The military-use roads were constructed by mobilized citizens and must have been hard to build, as everything would have had to be done by hand.

I watched all the events of the atomic bombing unfold from Nishiyama; I saw the atomic bomb being released from the airplane over the prefectural office and then watched as the wind carried it towards the Urakami district. (What I saw was) a round object hanging from a parachute and fluttering back and forth. As I looked on I said, “What could that be?” Then the parachute fell behind the mountains and exploded. There had been no sound; it just fell silently. But then blast winds stronger than any typhoon came raging through and in the next second everything lit up. I couldn’t open my eyes after that. In those days, almost all the houses in that region had straw roofs. At the instant of the flash of light, the roofs went up in flames and everything caught fire. The sight we saw from our location was that of dozens of houses burning. From that point, well, we left our lunches and tools up in the mountain and quickly fled down the military road in the direction of Yagami. As we went in and out of the mountain forest the sky grew pitch black and the sun turned a deep-red color. Then rain began to fall. It was oily rain. The white summer shirts we wore turned completely black. I think that was at around three or four o’clock. The sun was bright red and the mushroom cloud billowed out and out as if it was going to fill up the whole sky.

We must have wandered through the mountainside for hours as we fled. We were running this way and that. About twenty or thirty of the students from my class moved as a group. When we came to the district of Nishiyama 4-chome, we saw droves of bombing victims walking along the road from Motohara to the reservoir on the other side of the mountain. Everyone’s hair had been scorched by the heat and you couldn’t tell the men from the women. They must have felt relieved when they reached the edge of the reservoir because they all sat down there on a narrow road that was no more than two or three meters wide. The ones who were the worst off stuck their heads in the water of the reservoir and drank it. The number of people who died there was incredible. It was not just ten or twenty or so. They crowded along the edge of the water as if someone had lined them up there. There were people sitting at the roadside and also people lying down. We couldn’t tell if they were alive or dead. They were squeezed together so tightly that you to walk over them if you wanted to get by.

It was at that point that the teacher in charge of our group arrived at the reservoir. Apparently he had taken cover in a ditch when the atomic bomb fell and now he was covered in mud. When I said, “Sensei, what happened to you?” he answered, “I was lying face-down in a ditch.” I said, “Why don’t you take a dip in the reservoir?” Many of the people around the reservoir, the ones I couldn’t tell if they were dead or alive, were lying with their faces in the water. My teacher got right in anyway and washed off his muddy clothes.

My father had apparently been in a field at the time of the atomic bombing and had been lying on his stomach at the foot of a ridge. Because of that, he suffered no injuries at all. My mother had been inside our house. My older sister, who was enrolled in the municipal school for girls, had gone to work at the Mitsubishi arms factory in Saiwai-machi as a mobilized student. That day she had been told to go home however, and because of that escaped close-range exposure to the bombing. Our father returned home with his shoulders slumped, thinking that my sister was dead, but when he stepped into the front entrance and saw her lunchbox a wave of relief came over him. I arrive home late that evening. My father had grown worried when I didn’t come back for so long a time and went to the nearby grounds of Nagasaki University School of Economics to wait for me.

A water works tunnel carrying water to the Narutaki area used to run under the place near our house where a community center now stands. It had been carved into the rock. That tunnel was completely dry and we used to use it as an air-raid shelter. As our house had been ruined in the atomic bombing, my father took off the wooden doors and carried them over to the tunnel and laid them down so we could sleep there. At first, we intended to only have people from our neighborhood association use that shelter, but later people we didn’t know began showing up. They came one after another, saying, “Let us in!” There was no way we could refuse them, and soon the shelter was full of people. I didn’t count how many there were, but it was quite a number. After around a week had gone by, the open wound on the arms and legs of the injured became infested with maggots. Maggots were crawling around in the wounds of people who were still alive! There were no doctors around, so my father got some mercurochrome from our house and disinfected the wounds with it. As time went by, those people went off somewhere else. I don’t know if they made it home or if they died. In the end, we didn’t even spend a month in that gutter. We hired a carpenter to fix our house, which had been mangled by the blast winds. He used a vice to straighten out the bent sections and repaired the roof tiles. I think the repair work took two or three months, but in the meantime we lived in the tilted-over house as it was.

Rescue, Relief and Restoration Activities

Wood from the houses that had been dismantled on army orders was collected and, after it had been piled up on the athletic ground of the school of economics, lit on fire. Then the corpses that were piled up on flatbed carts were thrown on top. I don’t remember how many days that went on for. (The cremations) were conducted every day, starting soon after the atomic bombing. Bodies were cremated as they were brought in. And this wasn’t just done at that one location, but at places all over the city. Cremations couldn’t be done continuously at the same location, so the site would change from one place to another, and then another after that. The people who carried in wood kept bringing more. The people who brought in corpses kept bringing more. And then the fires would be lit. Ten or twenty were cremated at a time, and this was repeated over and over. Adults and children were cremated together. I don’t know what was done with the remains afterwards. As we were just sixth graders, we didn’t have to help out with those duties and only watched what was going on. I didn’t feel anything, however, not even when I saw the arms or legs of the corpses hanging off the carts. It must have been that I had grown emotionally numb after walking over all the dead bodies day after day.

After War’s End

It was days later when I found out that this had been an atomic bombing. I think I heard it said on the radio. Not every house had a radio, so we gathered at a neighbor’s home and that was where we heard the news. We also learned about the war’s end from the radio. That was right around noontime. What can I say – there was no show of emotion and no one cried, either. Everyone had grown numb to so many things.

Soon after the end of the war, the occupation forces arrived in (our neighborhood of) Katafuchi-machi. There were lodgings for stationed soldiers, and so we had two or three hundred foreign people staying there. I had a friend who had been repatriated after being born in the Philippines and he could speak English. Every day we went over to that lodging house together to play around. We were also given food to eat there. It was really good, I tell you. The army had supplies of canned food like curried stew and they used aluminum dishes instead of regular bowls. Everyone affectionately called me Botchan. I would go home with my pockets filled with the chocolate, cigarettes and other things I was given. Then I would give those things to other people. My father used to get angry and say, “I don’t like Americans. Don’t bring that stuff home.” In my father’s mind Americans were the enemy.

As school was out for summer vacation and there were no teachers around, we were on holidays for a long time. There were no male teachers then, only women. Later on, Nagasaki Commercial High School was built at the site where Saiseikai Hospital now stands and I soon went there to take my tests. I studied there for about a year and then transferred to the school in the district of Nishi-go (an area now called Aburagi-machi). In those days the streetcars only ran as far as Urakami Station, so I had to walk all the way to Nishi-go, which was a long way. The school was made of reinforced concrete, but the glass had all been smashed and only the window frames remained. In the winter, we put paper up in place of the glass in order to get through the winter. One of the kids at school was the son of a charcoal dealer and he used to fill his pack to the brim with charcoal and bring it with him. We would light the charcoal and then warm ourselves over it as we studied. There was no danger of fires breaking out as the flooring had already burned away, leaving the cement underneath exposed, and so our teacher didn’t say anything about it.

Oddly enough, I feel like I grew up without much hardship. Among my friends there were many children who went to junior high school but couldn’t carry on to high school. It wasn’t uncommon for kids to begin working as soon as they graduated from junior high. About half of the kids (in my class) did that. That was because they had to start earning money, and had nothing to do with whether they were smart or not. One friend of mine had a family tree that must have been about two-meters long and was the descendent of a minister at the Nagasaki Magistrate’s Office, but even he started working after junior high school and told me he wouldn’t be able to attend high school. No matter how privileged someone had been in the past, it didn’t mean anything after the war. It took everyone’s utmost efforts just to get enough to eat.

As for work, farming proved profitable. When I was around twenty I took over my father’s fields. My father had been a fulltime farmer and his back was bent over from carrying eighty or even ninety kilograms of things like pumpkins and radishes. As I had a small build, I didn’t think it would be good for me (to work like that), and when I told my father that I wanted change to growing flowers, he said, “Do whatever you like.” In those days there was a prefectural improvement office in the Zenza-machi neighborhood with technical experts specializing in both vegetables and flowers. I was able to learn from the flower specialists and then built my own greenhouses. During my busiest period I had 24 or 25 of them and was providing a constant supply to the flower market in the Shindaiku district.

Food Supplies in the Post-war Period

In Omura, there was an area called “The Korean Village.” From there, women known as “carriers” would fill ice packs with alcohol and then carry five or six of them on their backs and try to sell them in the city. My father liked alcohol and began drinking again soon after the end of the war. Alcohol was a rationed product that we shouldn’t have been able to afford, but we sometimes had five or six large bottles it in our home. The police knew about that and the patrol unit from the nearby police box would aim to come by our house at the time when my father was drinking. They always said, “If you don’t give us a drink we’ll arrest you!”

As we were a farming family, we never suffered for food. Even during the war we made osechi (traditional dishes served at New Year’s in Japan.) Locals would come to our fields to buy pumpkins and other produce and my father would tell them, “Take as many of the potato vines and things like that as you want.” Size was what people prized for vegetables, so we sent lots of pumpkins and other large produce items to the market. We would take lots of vegetables with us and return with clothing. Clothing was in short supply back then, so that was one way that people paid us.

Message for the Young Generation

Three friends of mine who were exposed to the atomic bombing at the same place I was passed away from leukemia when they were still in their thirties, which should have been the prime years of their lives. One of them entered a trading company after graduating from university and took a position in Germany. He was then stricken with leukemia and returned to Japan, where he passed away. As for me, I have never felt any physical effects from the atomic bombing.

I have heard that talks about the atomic bombing are now being given by people who didn’t experience the bombings themselves (due to the aging and passing away of the atomic bombing survivors.) I personally believe it is better to have atomic bombing survivors give such talks. I am now 86 years old and I have been told that if I continue at this rate I may live to the age of one hundred. If possible, I would like to become active in speaking out about my experiences.

Dictated at the speaker’s home in Katafuchi-machi, Nagasaki City on Oct. 8, 2019

No Matter What the Circumstances, War is Wrong and Nuclear Weapons are Wrong

As told by Shiroh Tomokiyo (93 years old)

| Shiroh Tomokiyo, a technician in the Department of Physical Rehabilitation (now the Department of Radiology) at Nagasaki Medical College, was inside the college hospital building when he experienced the atomic bombing. His superior was Dr. Takashi Nagai, who was an assistant professor at the time. Following the atomic bombing, he joined Dr. Nagai in the 11th Nagasaki Medical College Relief Unit (the Physical Rehabilitation Department unit led by Takashi Nagai) and took part in first-aid activities for the wounded. The conditions they encountered were explained in detail in Takashi Nagai’s book The Bells of Nagasaki. Mr. Tomokiyo lost his father (Haruo Tomokiyo) and many of his friends and colleagues in the atomic bombing. This year, Mr. Tomokiyo attended the Nagasaki Peace Memorial Ceremony for the first time. |

|

|---|

Before the Atomic Bombing

I graduated from Nagasaki Prefectural Keiho Junior High School and began working as a technician in the physical rehabilitation department at Nagasaki Medical College Hospital. Assistant Professor Takashi Nagai was the department head at that time. I was so busy when I worked at the hospital that I sometimes bathed in the patients’ bath and slept in the hospital beds.

In 1945, I was living in a public housing unit that my father, Haruo Tomokiya, rented for me in the Shiroyama-machi neighborhood of Nagasaki City. My father himself lived up in the village of Matsushima in Oseto Town, Nishisonogi County, where he was the president of the local credit union and a civic councilor. In those days, my father would often bring me rice when he came to visit. He liked alcohol and often drank in the evenings, with one of his drinking companions being Dr. Nagai. He would take alcohol with him to Dr. Nagai’s house and they would drink together, as Dr. Nagai liked drinking as well. Because of (their relationship) Dr. Nagai always treated me kindly. I also visited Dr. Nagai’s home on occasion and always took alcohol with me, as my father told me to do.

August 9, 1945

In the morning on August 9, 1945, I was on my way to work at the hospital and was in the vicinity of Inasa Bridge when I ran into my father, who had brought some rice from Matsushima Village in Oseto Town. He said, “I was just on my way to your lodgings to drop off this rice I have with me.” Then we parted ways.

At around 10:50, Dr. Nagai said to me, “Shiroh-chan, I know it’s early for lunch, but let’s go inside and eat,” and so I went inside the hospital.

When the atomic bomb was dropped, I was in the fluoroscopy room with another technician named Keisei Shi. We heard what I think was the engine roar of the B-29 ascending sharply after dropping the atomic bomb, but at the time we thought it was the sound of a bomb landing close by. At the same time, an orangey-yellow flash of light shot out and people were lifted off the ground by the horrific blast winds that came blowing through. Then everything went pitch black. The ceiling suddenly collapsed, so I quickly got under a large desk that was the size of a table tennis table. Shi said, “I think we’ve been buried alive.” After a little while, I felt my body grow wet and told Shi about it. He asked, “Do you feel hot or cold?” and I answered, “Cold.” Probably the water from an overturned bucket had spilled down on me.

In time, we came back to our senses and the two of us went upstairs to the x-ray room to look for Dr. Nagai. We found the doctor more-or-less well, although he had been hit by a falling book shelf and was bleeding. He said to me, “Tomokiyo-kun, I think Dean Tsunoh was off examining outpatients – could you go and check on him?” I went to the examination room and found Dean Susumu Tsunoh sprawled out on the ground along with all the students. The dean had a number of wounds, so I wrapped up his ribs and thigh (where he had broken bones) and then, in accordance with Dr. Nagai’s orders, carried him on my back to the hill at Anakobo Temple, which was in the mountainside behind the hospital, and laid him down on the ground.

Now that I was outside the hospital building I looked down on the city and saw that all the houses and everything else had been pulverized and reduced to nothing. I was stunned. I wondered if there was really a bomb that could have done all that. Later on, people started saying, “It was an atomic bomb! It was an atomic bomb!” and I understood that this was what an atomic bomb was. I thought how lucky I was to be alive.

Engaging in First-aid Activities for the Wounded

On the hillside below Anakohboh Temple and in the fields I administered first aid to the hospital patients and other wounded people. Dr. Nagai had also come to the fields below Anakohboh. He was bleeding from a terrible wound near his ear and (his head) had been bandaged.

The hospital was full of people who had been outside at the time and were now wounded. They were all calling out, “Please do something for me!” We told them, “Everyone is out back in the fields, so please go there.” Then we began leading those patients and wounded people by the hand to the fields out back, and it was then that I realized I had wounds on my face, arms and legs. There was not much we do in the way of administering first aid. So many people had gathered at the hospital and they were all pleading “Help me!” but there was no way we could look after everyone.

After taking Dean Tsunoh to the hill in front of Anakoboh Temple black rain started falling from the sky. We caught some of it in steel helmets and gave drinks to people who were lying on the ground nearby and crying, “Water, please!” Looking back on it now, I think it was a bad thing to do. Fortunately, we didn’t put any in our own mouths, as I later heard horrific things about that rain that made my blood run cold.

No food was available that night, but we fetched some water from a mountain stream and then boiled some of the pumpkins that were strewn around the field in our steel helmets and ate them. I remember that we also gave some of that pumpkin to the wounded to eat. Everybody was starving and ate with glee.

After August 10

There were scores of corpses on the hospital grounds. Following Dr. Nagai’s orders, we gathered up wood and cremated the bodies. I was with Keisei Shi, Head Nurse Hisamatsu and laboratory assistant Kunsan Shi. As Keisei Shi and I were the youngest, we were in charge of carrying all the heavy things.

The day after the atomic bombing, we moved away from the atomic wasteland and spent a night in the pharmacy department’s air-raid shelter, which was beside the ground of the medical college.

Three days after the bombing, the medical unit helped Dr. Nagai move to Fujinoh in the Koba district of Mitsuyama. There, acting as the Mitsuyama Emergency Relief Squad of the 11th Nagasaki Medical College Relief Unit (the Physical Rehabilitation Department unit led by Takashi Nagai), we continued to provide first aid. To get to Mitsuyama we passed Urakami Cathedral and the area where the interchange for Kawahira bypass is now. Some of the healthy people had gone to City Hall and returned with rations of hardtack and things like that, which we ate along the way. It was enough to fill our stomachs.

The 11th Medical Relief Unit spent almost two months in Mitsuyama. We went around to the houses of the wounded and tried to treat patients who had gathered in the area, but we had no medical instruments or medicine. Since I was an x-ray technician, I was not directly involved in the treatments and mainly helped out by doing physical labor. I had only just graduated from Keiho Prefectural Junior High School and don’t think I was much use in the relief activities.

After the atomic bombing, my older brother found the body of our father, who had been killed by the explosion, at Inasa Bridge (in the Takenokubo area.) Maggots were festering in my father’s corpse, which my brother and I then cremated. We put his remains in a can and walked all the way to Matsushima Village with them. There were no boats running and the distance was quite far, so it took us a half a day to get there. I remember it as being a really hard trip. In those days it would have taken three hours even if we went by boat. After returning to our hometown I suffered from diarrhea for about a month. As my mother was worried about me, she brewed tea made from persimmon leaves, loquat leaves and anything else thought to be beneficial and gave it to me to drink.

After War’s End

Just before the dropping of the atomic bomb, Dr. Nagai called for me and I went inside a building. I think that was why I survived. I feel apologetic to those who lost their lives. After the war, I felt that I should follow Dr. Nagai and continue doing work in the field of radiation. I felt that I owed my life to Dr. Nagai.

At Nagasaki Municipal Hospital, where I started working soon after war’s end, I was able to perform my duty as a radiologist and work my way up to the position of head radiologist. Up until the age of 75, I worked as hard as I could at Nagasaki Municipal Hospital, Jikei Hospital, Juzenkai Hospital, Sakura-machi Clinic and Nagasaki Yuhai Hospital. Later on in life my legs grew weak, but my wife Hitomi would drive me to work and pick me up every day, and I believe it was thanks to her that I was able to carry on with my employment. I am grateful to my wife. It is also due to her that I am still alive. If I didn’t have my wife I would not be here today. The director of Nagasaki Yuhai Hospital agreed with me, and when I retired from my position there he told me, “Half of your retirement pay belongs to your wife, you know.”

After the war, I managed the Nagasaki Nyokodo Society, a group set up to honor Dr. Takashi Nagai. I also enthusiastically coached youth soccer until the age of 55, having been a player myself during my days at Keiho Junior High School.

Health-wise, I have suffered from illnesses such as jaundice, slipped discs, heart trouble, suspected lung cancer, bladder cancer and bowel cancer. There have been times when I even sent letters to the national government detailing my illnesses.

Up until now I have lived my life for myself. From now on, however, I intend to live in honor of Dr. Nagai, as I am the one who was closest to him (at the time of the atomic bombing.) Accordingly, this year I took my wife’s advice and attended the Nagasaki Peace Memorial Ceremony for the first time, feeling that it was something I had to do while I was still able to walk. In my mind I was thinking, “Thank you, Dr. Nagai.”

Message for the Young Generation

War is absolutely wrong. I hate it. It is wrong no matter what the circumstances. Nuclear weapons are also wrong. Not having war – that is the best thing. While it seems like nothing can be done about all these countries possessing nuclear weapons, I would like young people to think about things on behalf of all those who have lost their lives in war. Shouldn’t we all be thinking about these things together – about how nuclear weapons must never be used a second time?

It was awful to lose my father and many of my friends in the atomic bombing. I feel guilty about surviving all alone while so many others, including those who I am indebted to, passed away. Dr. Nagai consoled me about this, saying simply that I had been the recipient of God’s help. In the time I have from now on, I hope to tell people more about Dr. Nagai and all the things I have learned.

This account was recorded at Mr. Tomokiyo’s home on October 30, 2019

Reference materials:

Nagasaki no Kane (The Bells of Nagasaki); Takashi Nagai

Genshibakudan Kyuugo Houkokusho (A Report of Relief Efforts for the Nuclear Bombing); Takashi Nagai

Nagasaki Ijinden: Nagai Takashi (A Biography of Nagasaki’s Great Man: Takashi Nagai); Kiyotaka Ogawauchi

Nagai Takashi Hakase to Kyuugo Katsudo no Keiken: Tomokiyo-san; “Sensei Arigatou” (My Experiences Conducting Relief Activities with Dr. Nagai; Mr. Tomokiyo says, “Thank you, Doctor”); a newspaper article published in Nagasaki Shimbun on August 10, 2019

Nagai Hakase to Tomo ni; Dai-juu-ichi Iryoutai Kyuugohan no Ichi-in to Shite (Working alongside Dr. Nagai as a member of the 11th Medical Team Relief Unit); as told by Keisei Shi in Nagasaki Ika Daigaku Genbaku Sensai Fukkou Nikki (A Diary of Reconstruction Efforts at Nagasaki Medical College following the Atomic Bombing Disaster) by Raisuke Shirabe

Nagasaki Ika Daigaku Genbaku Kirokushu; Dai-ichi Maki (Nagasaki Medical College Records of the Atomic Bombing; Volume 1); see the memoir of Matsuko Kaneko on p. 500 and the memoir of Shisono Hisamatsu on p. 502

A Sad Parting from my Boyfriend

As told by Fusae Genjoh (95 years old)

| Ms. Fusae Genjoh is now 95 years old and living in the neighborhood of Shimonishiyama-machi in Nagasaki City. On the day the atomic bombing she was at her home in Rokasu-machi (which also had a storefront) with her mother and her three younger brothers, all of whom were exposed to the blast. The staircase and other parts of the house collapsed. She took her mother (who suffered from tuberculosis) and her brothers and sought shelter at her boyfriend’s home in Yanohiro-machi, but he had passed away. They then walked through Himi Tunnel and headed for (the neighboring city of) Isahaya, stopping on the way to spend the night at a home in the countryside. The following day they walked to Isahaya Station and caught a train back to their home in Rokasu-machi. She and her boyfriend had promised to go see a movie on August 9, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing, but that was not to be. |

|---|

Before the Atomic Bombing

I was born in Rokasu-machi, Nagasaki City in 1923, in a home located beside the third torii gate of Suwa Shrine. I lived there with my parents (Tetsunosuke and Shizue Genjoh) and my three little brothers (Shiroh and twins Kohichi and Shuichi). Shiroh worked in the administrative department of Mitsubishi’s training school, which the twins were enrolled at. My mother was my father’s second wife.

1945 was a lively year for Suwa Shrine and so my family opened up a small shop selling picture postcards, souvenirs and toys. My father passed away from lung cancer in January of that year, at the age of 71. Then in August my mother grew thin from tuberculosis and had to stay in bed, leaving me to manage the store all by myself at the age of just twenty-one.

Food was scarce during wartime, so I would go off to (the neighboring municipality of) Isahaya to barter for what I could get. From Isahaya Station I would walk one ri (a distance of about four kilometers) to the home of an underling of my father who worked for the Japan Red Cross and the people there would share some of their (food supplies) with us.

One day, I was waiting at Isahaya Station with a load of potatoes on my back when a man called out, “Hey, you! Come over here for a minute. Don’t you know what day it is today?” I answered, “Yes, I do. It’s the Day of Imperial Reverence (this was commemorated on the eighth of every month to mark the start of the Pacific War on Dec. 8, 1941.)” Then he said angrily, “And you think it’s alright to go out procuring things on that day?” I’d been thinking that we had to eat or else we would starve, but the man said, “Now, get on your way.” So I hid the potatoes under a station bench and went home without them. The next day I went back to Isahaya Station to pick the potatoes up. We boarded trains through the windows in those days, not the doors, and so after I got the bag of potatoes I put it through the window before climbing in myself. But I ended up landing right in the lap of the person sitting in that seat. What a distressing situation that was!

One day, my mother and I trespassed on a field on Mt. Kompira and tried to dig up some potatoes, but all we pulled up were leaves. Thinking back on it, it seems like it was hell in those days. When I recall those times I really hate war.

The Day of August 9, 1945

August 9, 1945. As the hour of eleven rolled around, my mother and I were eating whatever food we had at the house and drinking tea. Then a light flashed and a loud boom sounded out. I said, “That must’ve been a fifty-kilogram bomb!” and we grew panicked. I was so scared that I dashed over to our home air-raid shelter in just my bare feet. Once I was inside I yelled back to my mother, “Mom, get in here now!” Our lives were the most important thing at that point, and so my mother came into the shelter without stopping to pick up any of our possessions.

My brother Shiroh, who was eighteen at the time, worked in the administrative department at Mitsubishi’s training school. He had worked overtime the previous night and didn’t come home until that morning. (At the time of the bombing) he was sleeping up on the second floor and when he realized that the staircase had blown away, he yelled down, “Sis, what happened? I can’t get down!”

“Just get down here anyway you can,” I yelled back. There was nothing else I could say.

I grew worried about my fifteen-year-old twin brothers (Kohichi and Shuhichi), who had been outside playing with some of the neighbor kids, and went out to the street to look for them. One of them had been hit by a shard of glass and had a wound to his head. I was thinking I should take him to the first-aid center at Katsuyama Elementary School, but a man who was looking up at the sky and frantically circling the electric pole outside our house was screaming “Enemy planes! Enemy planes!” and so my three brothers and I dashed off for the air-raid shelter in front of a liquor store named Takeyama.

A man in his thirties or forties who had come down from the Tateyama district entered the shelter ahead of us. He was a frightening sight. His face seemed to be split right in two, (his skin) was a pale-bluish color, his body shook like a leaf, and blood poured out of his wounds. His eyes had a pleading look, as if he was begging for any kind of help he could get, but I was too terrified to even say anything to him. (Compared to those wounds) my brother’s injury didn’t seem serious at all. I was so flustered that I didn’t even have the presence of mind to go outside and shout, “There’s a wounded man in here!” Not knowing what to do, I left that man behind and fled the shelter with my brothers. To this day, I find myself thinking about him.

Inside one of the other air-raid shelters I saw a young mother carrying a headless baby on her back.

At the first-aid center at Katsuyama Elementary School wounded people who had been placed on wooden doors were being carried in on after another. Thinking that my brother’s wounds were nothing serious, I gave up on the idea of taking him inside that center and returned home to where our mother was. Then my mother and I had a discussion about what we should do from then on.

A Sudden Parting from My Boyfriend

Actually, I had promised the boy I was seeing at that time (who lived in Yanohira-machi) that I would go to Shindaiku and see a movie with him on that day (August 9). Noqw I thought we might be able to take refuge at his house, and so I took my mother and my brothers there. We arrived to find that the father had gone out looking for his son (my boyfriend), who was employed at Mitsubishi Steelworks.

After some time had passed, the father returned home with the remains of his son placed in a box. Great numbers of people had been killed at the factory and, unable to tell whose remains were whose, he had just taken the bones of someone he thought might have been his son and brought them back with him. His younger sister looked at me and then seemed to break down, saying, “You know, my big brother put his best clothes on when he went out today.” Upon hearing that, there was nothing I could say or do. Knowing that he had been looking forward to going to the movie with me and had dressed up in his best outfit left me speechless. I couldn’t even get myself to fold my hands in prayer before the box with his remains.

Thinking that it was not right for us to stay there, the five of us left the Yanohira neighborhood and returned to our own home in Rokasu-machi.

After we got back, a young woman who was the daughter of an executive at the Eighteenth Bank came by with a child on her back and asked for help, saying, “They won’t let me into my house! What should I do?” But I had my own sick mother to attend to and didn’t think I could afford to help anyone else just then, so all I did was listen to her talk and say “Yes, yes” from time to time. I still think about that person too, and wonder what happened to her.

Evacuating in the Direction of Hongouchi and Himi Tunnel

Then we received a bulletin from general headquarters (which was located at the place where the Nagasaki branch office of the Bank of Japan now stands) that read “All girls and women must evacuate!” My mother said, “I’m ready to face whatever comes, so you evacuate by yourself,” but there was no way I could run off and leave my sick mother and my little brothers behind. So I took a baby carriage from an uninhabited house in the neighborhood and placed my mother in it along with a supply of rice and other foodstuffs to last us for a little while. Then my three brothers and I pushed it along as we randomly fled in the direction of Hongouchi. There were streams of people evacuating along with us. Then a Japanese Army truck coming from the other side of Himi Tunnel passed by us and blared out the message “Don’t be fooled by rumors! Head back to your homes!” Thinking back on it now, it seems like a scene from a movie. We continued on with hollow eyes, however, thinking we should at least flee the city.

The baby carriage began breaking down along the way and when we got to the end of Himi Tunnel I said, “You’ll have to walk now, Mom. There’s no other way.” She responded by saying, “I can walk. I’ll do what it takes.” As we walked on, the number of people around us gradually grew less and less.

At one point we decided we would have to sleep outdoors that night and, looking to the left, saw a splendid detached house with a large gate. I went up to it and said, “Excuse me, but would it be alright for us to spend one night under the eaves of your home?” The people there were kind and ended up letting us stay in a four-and-a-half tatami mat room near the entranceway and even put out futons and mosquito netting and served us rice balls. I still have never properly thanked (those people) whose house we spent the night at. After eating the rice balls, my brother Shiroh said, “Sis, I can’t see.” He was a clever boy, but a little on the sly side and I thought he might be trying to trick us. Afterwards, however, I thought that the poor boy must have been suffering from night blindness due to malnutrition. That night we managed to stave off our hunger with a rice ball.

The Day after the Atomic Bombing

On the next day, August 10, we walked towards Isahaya. Along the way, the air-raid alert sirens sounded to announce that enemy planes were coming. Someone shouted, “Take cover in the fields!” and so we hit the ground. Another person was injured by machine-gun fire and carried away on a stretcher. We then went to Isahaya, but didn’t know where to go from there and finally said, “Let’s just go back to our own home.” At Isahaya Station we bought train tickets and returned to our house in Rokasu-machi. When we checked through our home again we saw that the staircase leading to the second floor had been blown out back and crushed.

Back at home, the men and women in the neighborhood told us, “You shouldn’t have gone away like that. You would’ve been better off not fleeing.” That was because the local headquarters had apparently been distributing lots of relief supplies (while we were gone.)

After that, we decided to evacuate to our parents’ family home in Oita Prefecture. We went to City Hall to get certificates so we could buy tickets for the train, but everything was in a state of confusion there and at that time nothing could be had. With nowhere to go, we ended up staying at our home. We went to work repairing the home in Rokasu-machi and lived there after the war as well.

After the War

My mother passed away after war’s end, in the year after the atomic bombing. (She was 53 years old.) My brother Shiroh gained employment doing office work, but he passed away at the age of 33. My twin brothers worked as shipwrights in the Naminohira district and are still living now.

Through an introduction from our neighborhood association, I was able to get married at the age of 22 to a man who repatriated from the Philippines. He was someone who was clever and good at English. He had been working for a funeral company, but I told him “I don’t want to get married to someone who works in the funeral business” and by the time of our wedding he had become an interpreter for the prefectural government. After getting married we lived in my family home at Rokasu-machi, but just one year later he drank some methyl alcohol and passed away as a result.

I then began working as a typewriter at the house of a member of the House of Councilors. I was really treated well there. Later on, I remarried after being introduced to someone by a neighbor. One day, when I was around 35, I set out with my daughter to take an exam to become a licensed cook of the school meal program, which I passed. I ended up working for 50 years, right up until I reached retirement age.

Message to the Young Generation

Above all, (we need) peace. War is the only thing I hate. I really hate it. War is no good. With nuclear weapons the whole world will be ruined. I find myself thinking that my grandson-in law, who is a Doctor of Engineering at a university, needs to invent some kind of wall that will send incoming nuclear missiles bouncing back to the countries they were launched from so they will explode there instead.

Dictated at the speaker’s home in Shimonishiyama-machi, Nagasaki City on Sept. 9, 2019

Artist: Kozo Aida

Artist: Kozo Aida

Property of Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

I Can’t Forget that Tragic Experience and the Loss of my Mother

As told by Masako Akabae (94 years old)

| Masako Akabae (maiden name: Masako Maruo) currently lives in Ohyama-machi in Nagasaki City. She is 94 years old. At the age of twenty she experienced the atomic bombing while working in the office of the payroll department of the Saiwai-machi factory of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipbuilding Plant. She managed to slide under her desk and narrowly escaped death. Her mother, Misa Maruo, passed away at the family home in the Matsuyama-machi neighborhood. Her father, Isematsu Maruo, had gone to the Ohata district as part of his job and escaped injury. Masako and her father then buried her mother’s remains in a graveyard in Mitsuyama-machi. To this day, she cannot forget about the tragic experience of that time. |

|---|

I was born on November 26, 1924, at 118 Matsuyama-machi in Nagasaki City, which is now the site of Ohkawa Ryu Furniture Store. Matsuyama-machi was the area that became the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. My maiden name was Maruo and my father, Isematsu Maruo, ran a lumber business. Along with my mother, whose name was Misa, there were three of us in the family.

In 1945, when I was twenty years old, I was working in the office of the payroll department of the Saiwai-machi factory of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipbuilding Plant. In those days, the functions of general affairs, accounting, operations and management were all separate. I worked in operations, confirming work records and passing them on to the people in accounting. I was also one of the group that would go to the factory and hand over pay envelopes to workers who were standing in lines.

The Morning the Atomic Bomb was Dropped

On the morning of August 9, 1945, my mother was giving my father a crew cut with a pair of clippers. At around ten o’clock she said to me “You’d better hurry off now because I know you’re busy at work” and so I left home. Looking back on it, that was our final parting. I always took the streetcar, but for some reason on that day I walked as far as the office in Saiwai-machi with Ms. Kurokawa, a colleague who lived across the street from me. The office building was a large wooden structure two stories tall.

The Moment of the Atomic Bombing

We reached the office in Saiwai-machi and were ready to get down to work when a senior worker named Mr. Nishimura came down from the second floor to have a meeting with us. Right at that instant, the boom sounded. I didn’t sense any flash of light or blast wind, but there was a loud bang. My body flipped right over at that point, but luckily I slid under a desk. Ms. Kurokawa was also under a desk and Mr. Nishimura had been thrown on his back. Everyone around us had been pierced by shards of glass. Ms. Kurokawa had been stabbed in the back by pieces of glass and she was unable to get them all out at that time. It ended up taking years to have them all removed. I fortunately escaped without any wounds, but for some time after that I had a condition like amnesia and couldn’t remember the names of people I was talking to.

While I was under the desk I said prayers. Without really thinking I found myself murmuring, “Mother Mary, please help me. Why do I have to die here? It will make my mother so sad if I die.” I was terrified. What I felt was even beyond terror. The chief of the general affairs department was sandwiched between debris and could not be freed without having his arm cut off. Someone cut the arm off with a saw and pulled him out, but he passed away from the loss of blood. That was really shocking to me. He had been a kind department chief.

Fleeing out of the Building

I was under the desk wondering, “What should I do? What should I do?” when some men started shouting “Everybody out! Fires are breaking out!” Mr. Nishimura said to me, “Grab hold of my leg and I’ll pull you outside. I’m getting out now. Don’t let go of my leg!” I grasped onto Mr. Nishimura’s leg for all I was worth and sometime later found myself outside. By then my monpe trousers were torn and ragged. It had taken every ounce of strength I had to keep crawling along.

Outside, I saw something that really took me aback; a woman who was covered in so much blood that she was bright red was sitting up in a tree. Ms. Kurokawa, Mr. Nishimura and I then went over to the air-raid shelter at the foot of Shoutokuji Temple, which was across the way from our office, and stayed there a while. The shelter was big enough to hold about twenty people. Among the others already inside were some large foreign prisoners of war.

Mr. Nishimura went back to try to rescue some of the other employees. Factory workers were coming and going from the shelter.

After about ten minutes had passed, I left the shelter and went over by the bridge to relieve myself. Mitsubishi Hospital and all the other buildings in that area had been flattened to the ground and fires were raging in the wreckage. Men who had torn strips of cloth off their shirts and were holding them over their mouths ran to the rescue. My office building had been flattened as well.

There was one man who said, “Hey, you! Run through the fires to get to the other side. No fires are burning there.” I thought that was a ridiculous idea because my head and body would have been scorched, and so I told him, “No way!” That really irritated me. Afterwards, I returned to the shelter.

After I had been in the shelter a while I heard the BAM, BAM, BAM of gunfire. I looked up at the sky and saw a reconnaissance plane flying by at low altitude. It circled back a number of times, taking aim at the shelter and firing. It was detestable and horrible thing.

The state of the city was such that it felt like a living hell. Dead bodies were piled up outside the air-raid shelter, including a dead baby being nursed by a woman. Soldiers who came down from Mt. Inasa began performing various relief operations.

Girls from the Volunteer Corps Who Were Losing their Hair

Sometime later on, three or four girls from the volunteer students’ corps came walking towards us from the direction of Nagasaki Station. I said to them, “Please drink some water.” Spring water was flowing nearby, and when I told them to take a drink, they did. When I got a good look at them I saw that their hair had fallen out and they were almost bald. They seemed otherwise healthy, except for the fact that they were balding. I told them I thought their hair was falling out and they answered, “Oh no! It is, isn’t it?” I felt so sorry for them.

Moving to the Air-raid Shelter at Suwa Shrine

I had left my box lunch in the office, but Ms. Kurokawa had brought hers with her when she fled. She kindly shared it with me and so we ate together.

A little while later, an acquaintance came over and said, “It’s dangerous to stay here. Let’s go over by Suwa Shrine.” So Ms. Kurokawa and I headed off for the shrine. There was a small air-raid shelter in the stone wall at the foot of the shrine, and, thinking that the fires would not reach that far, we spent the night there.

The Next Day: August 10

Before dawn broke on August 10, I was already beside myself with worry about my home in Matsuyama-machi. That being the case, Ms. Kurokawa and I set off on foot for our homes in Urakami. We kept away from the burning areas as we walked. It was probably getting on for noon when we came across some people we knew coming from the opposite direction. “Ms. Maruo,” they said, “Your home got destroyed too.” All I could reply was, “Ah, is that so?”

We rushed over to my home in Matsuyama, where my mother had been reduced to skeletal remains. I sobbed and sobbed in front of her bones. When Ms. Kurokawa went to her own home she broke out crying as well. Apparently her mother’s corpse was under her sewing machine, where she had fallen. My aunt and her children also lay dead at the entrance of my house. They had evacuated from Yokohama and were living in (Nagasaki’s mountainside district of) Mitsuyama-machi. I remember all these things as if they happened yesterday. How sad it was. I cried and cried, completely unconcerned with how I looked.

My father survived because he had been running an errand at Aoki Lumber in Ohato the day before.

In the kitchen area of my house there was a large wood-fired bath that was always filled to the top with water and firmly held in place with concrete and bricks. It was now flipped over and had a huge hole in it. When I saw that I thought, “The bomb must have exploded right around here.” There was a lot of wood around our house because we ran a lumber business and supply center, and it continued to burn for days after the atomic bombing.

Urakami Cathedral was destroyed as well. That came as a real shock to me. Nothing remained standing in that area. My home had burned down and my mother was just white bones. Charred corpses from that area were piled up and cremated one after another.

After that I managed to get over to the home of my uncle (an uncle on my mother’s side) in Mitsuyama-machi. Sometime later, my father came there as well.

On the night of the tenth, a male coworker of mine named Tamagawa came riding up to see me on his bicycle. I said, “It must have been hard to get here. You did well to find this place.” My father told him “You should stay and spend the night” and so Tamagawa stayed overnight with us. He left for home at around five o’clock the next morning, and, as he got on his bicycle and set off down the mountain path, I called out, “Be careful on the way back!” He collapsed soon after he arrived home, however, and passed away after that.

Later on, my father and I placed my mother’s bones in a box and took them with us from (our home in) Matsuyama-machi to Mitsuyama-machi. Then we went deep into the mountainside of Mitsuyama and dug a hole to bury them in. My family was originally from Mitsuyama and we were all devout Catholics.

Happenings in the Post-war Period

The American Occupation Forces landed less than ten days after the dropping of the atomic bomb, and soldiers came riding into the Oka-machi area in trucks. Ms. Kurokawa and I went to Matsuyama-machi to pick up rations and after we put them in our bags and were walking away some soldiers teased us with catcalls of “Whoo, hoo!” Fearful and thinking that they might kill us we ran away, diving into a ditch to hide. The ditch was filled with so many roof tiles (and other debris), however, that we couldn’t really hide ourselves. There were no other people around and nowhere else we could run to. To this day, I still remember how terrified I felt.

After war’s end, the office I worked at in Saiwai-machi was closed down and an inquiry desk for employee was set up. I put on my straw sandals and walked there from Mitsuyama-machi. When I asked, “Don’t we get any severance pay?” the two men in charge answered, “No.” It was at that time that I heard that Mr. Nishimura had passed away. As I had been planning on going to the Nishimura’s house to thank him for rescuing me, this came as a real shock to me and I went weak in the knees. Mr. Nishimura rescued many people on the day of the atomic bombing.

My father and I lived at my uncle’s house in Mitsuyama-machi for the first two years after the war. My father gave up the lumber business. There was hardly any food available in those days and we mostly ate potatoes. I would go all the way to Matsuyama-machi to get food rations like white beans and canned mackerel, and then walk all the way back to Mitsuyama-machi to give them to everyone to eat.

Two years after the atomic bombing we built a new home for ourselves in Matsuyama-machi.

Suffering from Atomic Bomb Disease

After the war, I got married and went to live in Kokura (in Fukuoka Prefecture). At one point I grew as thin as a rail and suffered from liver trouble. At the hospital I attended they told me, “It’s a case of atomic bomb disease.” Back then, I would get fatigued while walking up the stairs at the department store stairs and couldn’t climb them all at once. I had to stop and rest on each landing as I made my way up. My husband turned white when I told him I had atomic bomb disease and said, “We have four children now; what are we going to do if you die?” The doctors at the hospital said that someone in my condition shouldn’t have any more children.

In Kokura, I would sometimes get dirty looks when I showed my atomic bombing survivor (medical insurance policy) booklet. One time, the wife of the landlord where we lived turned to my husband and said, “Mr. Akabae, how could you take someone who experienced the atomic bombing as a wife? You’ll have four children to take care of if she dies.” At that instant, I thought, “You think I’ll give up like that? I’m gonna bring up my four kids.” I may have been thin, but I was strong-willed.

My Message to the Young Generation

Wars should not be waged. When I lived in Kokura, I never wanted to think about the anniversary of the atomic bombing when the day of August 9 came around each year. I would not even want to watch or listen to the news. Now we have peace, but back then conditions were miserable.

In the air-raid shelter I stayed in a man from my office named Araki shared cigarettes with a foreign prisoner of war and treated him kindly. After war’s end, that man came back and, unable to forget the kindness he had been shown, said fondly, “Araki-san! Araki-san!” So there were things like that as well. It is best for us to get along with each other in peace.

As an aside, both of my parents were from families that had been Catholic for generations, and our family was close with the late Takashi Nagai, the famous “doctor of the atomic bombing.” He often presented us with pictures and calligraphic messages that he had made. He was a very kind doctor.

Recorded at Ms. Akabae’s home in Oyama-machi, Nagasaki City on September 30, 2019

An aerial view of Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipbuilding Saiwai-machi Factory;

An aerial view of Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipbuilding Saiwai-machi Factory;

taken from the airspace over Zenza National Elementary School

U.S. Forces photograph

Property of Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum